Laird: Once we figured out we could stand on it, I asked the guy if we could borrow the setup and promised we wouldn’t damage the foil. We separated the original board and chair and stuck the foil on a wakeboard. Being physically connected to the setup seemed like a really important detail, and since we were snowboarding at the time, we put boots and bindings on it. The board flexed and the foil sucked, but because of the boots we could get up and fly. That first prototype allowed us to catch a wave on a day when there was a little surf. Once we realized that we could use wave energy, that lit us on fire. Going from the first feeling of riding a hydrofoil, to figuring out we could stand on it, to learning it was possible to ride a wave’s energy — that process took about a year. The next steps were to buy parts and pieces of Air Chairs to make more prototypes. When we called Mike Murphy and told him we were standing on it, he said “if you are, I’m going to sue you…”.

Kjell: Wow!

Laird: So, naturally we kept riding them! I think he was discouraging us because of liability reasons if we broke our necks. Over time, we created a relationship with the guys who bought Air Chair. Through that, we were able to get parts and pieces. All our setups were these Frankenstein combinations of bindings, boards, and foil pieces. Overall, it was a bit of a discouraging process, and at the same time kiting and stand-up paddling were growing and distracting us. I think All Aboard the Crazy Train (2006) showed us foiling at the stage where we were going out and riding waves, and that was amazing for the time. After that, the fire kind of wore out as far as other people’s interest. I ended up having a giant day at Spreckelsville which is depicted in the book The Wave. There were no photos, only eyewitnesses. We know the waves that day were as big as anything ever surfed. I had a moment where I realized planing hull surfboards were incapable of truly riding the biggest waves — surface tension, texture etc — and that’s when my personal focus shifted completely to foiling.

When I moved back to Kauai, I pursued foiling every day. I sent a video to Dave Kalama that definitely rekindled his fire. For the next eight years or so, it was basically me just building and riding custom equipment. Outside interest was pretty low, which usually happens with sports at that stage in development. Even today, you see that with tow surfing when Kai Lenny tows at Jaws and suddenly it’s a revelation. We spent 15 years towing giant Jaws, but all these things ebb and flow. What really changed foiling was when kiteboarders started getting on them. It’s always about the ease of entry, and the power source with kiting made that a lot more accessible. As kites got better and better and they started adding foils, foil development also sped up.

Remember that for the first ten years, we were building one-off prototypes made exclusively to tow in giant surf — there was no production. At the time, we were working with Dave Kalama’s uncle and the Maui Fin Company guys to build wings out of metal and G10. We got pretty far with those incremental changes. Once the GoFoil guys came onto the scene alongside the kite foilers, things really started to pick up. They were experimenting with fatter, lower speed foils which allowed for smaller wave riding. It was a reverse evolution where development went from giant waves back down in size, but that made sense given that we’d come from foils designed to ride 30mph behind boats. Those would never work in regular surf.

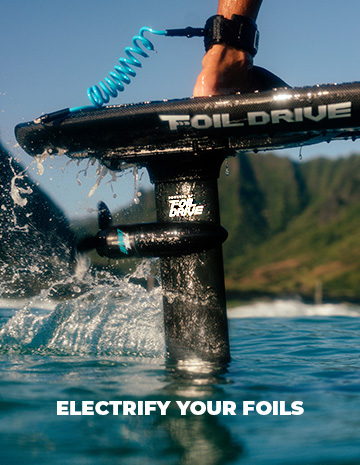

Somewhere along that timeline I tried Alan Cadiz’s stand-up paddle foil board out in California. The first day was easy flying and I had to have the board. He ended up being kind enough to pass it along to me. In the interim, Nick at Lift saw All Aboard the Crazy Train and decided to go to school to build foils. He came from the kiting world and set out to build an electric foilboard. Production wise, foiling really grew as a result of these new disciplines. Their power source made foiling way easier to learn than on giant waves.

Terry Chung and Nelson Kubock really helped develop things on Kauai. We all saw the same thing, shared a vision. It was like the original strapped crew on Maui, things were so productive. It’s a think tank where you’re together and can build off each other’s passion and ideas. That part is really interesting. It used to be just a few of us, now it’s 30 different companies, there’s the magazine, there are tons of disciplines — it’s all just grown into something normal. It’s a cool process to watch a vision come to fruition.

Kjell: You mention Terry and Nelson. Who were a few of the other people around that helped you drive this thing forward in the early days?

Laird: Obviously the Air Chair and Sky Ski equipment enabled us to get started. We just needed to get the stuff, not reinvent the wheel, and apply it to our situation. We had a friend, Stan, who worked with remote controlled airplanes, and he had an influence. We knew the America’s Cup engineers over at Oracle who had ideas along the way. Dick Brewer certainly was a big piece. Terry Chung is a master surfer and waterman with craftsmanship at the highest level, and his dedication and consistency was a critical element. Nick at Lift has been super supportive on the back end of things. Of course, Alex Aguera and the engineering going on at GoFoil is a big piece of the puzzle. Jimmy Lewis, Dave Kalama’s uncle, Bill Hamilton — my stepdad — all these guys were influences along the way. Some had to do with performance, some with tinkering, some with engineering. Ultimately it came down to application on the water.

Kjell: What’s your take on the c.2016 Kai Lenny videos and subsequent explosion in foiling’s popularity? That’s when foiling really came into the public eye.

Laird: What happened was, a larger group of people got to experience foiling. For those of us who had already been doing it in all kinds of conditions, there was nothing unusual about these videos, at least from our perspective. They showed just the tip of the iceberg. For example, we’d been towing into barrels at giant Peahi for ten years on planing boards, but then we go to Teahupoo and ride a freaky wave and suddenly it’s a big deal. These things can go from under the radar to exposed really quickly. With the development of anything new, this kind of cycle is normal. The second part is coming up with equipment designed for everyone to use, and developing disciplines that everyone can do. If the only flying device is a rocket that goes straight up, you’re going to have five people willing to try it, but if you invent the airplane, then it reaches a broader audience. The ability to go slow is a huge component. Not requiring that high speed energy opens foiling up for a lot of people. Of course, Kai is a fantastic ambassador for the sport, partly because he makes it look easy. That’s a deception of all the great athletes; they make things feel more accessible, so people are willing to try.

Kjell: Accessibility is a double-edged sword. We’ve got foilers of all experience levels in lineups today, and it’s controversial. What’s the long game with that as far as safety and social sustainability?

Laird: There isn’t a straight or easy answer to this. In surfing, we need freedom. You don’t want to tell people what they can and can’t ride in the ocean. Whenever you go into an area with a lot of people, it demands a certain skill level. If you’re driving a car and plan to go on the freeway, you better know how to drive. We don’t have licenses in foiling, but there’s the unspoken license of knowing how to control your vehicle. Surfing is a dangerous sport. I’ve been crushed, speared, and harpooned by every board imaginable, usually by other people. When you enter a lineup – or the ocean at all – it’s dangerous. Of course, foils accentuate that, but so do pointy boards and sharp fins. When people don’t know what they’re doing, they need to be in the beginner’s zone where nobody else is around. People who don’t know what they’re doing are more dangerous than people who know what they’re doing on dangerous gear.

Whenever I talk about lineups, I bring up Makaha. You go there and they ride everything. They’ll take a 2,000lb canoe right through the middle of the lineup, and if you don’t know how to get out of the way, you might get hit. That’s a real Polynesian lineup. And sure, while foiling lets you ride waves that don’t exist, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be able to go to a lineup at a great spot and foil, as long as you know what you’re doing. Often, I’ll be out at a crowded lineup and foiling ten places on the wave nobody else wants. It’s harmonious in a way. Just don’t be a ding dong; I don’t condone morons. It’s important to remember that this is the ocean, and stuff happens even to the best of us. When you leave the shore, you’re taking that responsibility into your own hands. If you’re not prepared for that, then don’t go out.

Kjell: Speaking of riding parts of wave that others aren’t looking at, how about downwinding and winging? Are you on that program?

Laird: Yeah, of course, but it’s all about where you are and what you have available. Downwind and winging are perfect for places that are windy like the Gorge, Maui, and the Canaries. I just recently started playing with winging, and it’s the easiest of all the disciplines I’ve tried because the foil feels the most tame. There’s something about the wing that really holds the foil in a nice position. For me though, because I like waves and am a surfer first, I really want to ride groundswell. We originally downwinded on Maui because of a lack of surf, not because we chose to do it over surfing big waves.

Whenever I teach someone to foil, I say it’s best behind a boat or on an e-foil because of the consistency. Then you get good and can go out in the surf or with a wing, but there’s nothing like a motor to create consistency in the beginning. I’ve been training this young big wave surfer, Luca Padua, and I taught him to foil on an e-foil. As soon as he went to a prone foilboard, boom, he was up and flying the first day. Tow foiling seems to still be the hardest discipline to master, mainly because of the reaction time. When you’re going full speed without any handlebars, reaction time becomes more relevant.

Kjell: Training that reaction time is definitely relevant if you want to actually ride and not just survive.

Laird: It’s the same thing as going 50 or 100mph. You get tunnel vision the first time. If you train for 100mph then go 75, you get time and everything opens up. Towing is a beast, and you can be the most versatile, do it all winger/prone/SUP rider, but as soon as you get towed onto a big ol’ wave, you’re gonna be surprised. SUP surfing is a dream, though. Try catching a wave for a mile and a half and prone paddling back on your 4’0, then tell me how many of those you get in a day!

Kjell: I hear you. I did a downwinder on the wing this past weekend which was originally supposed to be five miles. It ended up being over twenty because we had such a good time going back and forth across bumps. One of those mind-blowing sessions.

Laird: It’s freedom. In the early days, we held the bridles on small kites, kind of like wing dinging. Winging today seems like a natural evolution of that with proper handles.

Kjell: So big waves are your focus, but how do the e-foil, prone, and SUP foiling tie into that? As you’ve pointed out, towing is pretty distinct.

Laird: I use the e-foil as a training tool. Training for speed and reaction time when there’s no surf. It’s a highly productive device for that. If I crank for one hour on the e-foil, my legs are blown and my stamina increases for riding long waves. My goal with foiling is speed, distance, and size. Big waves are cool, but long, fast waves are what I go for. I get that a little bit with the e-foil. I can simulate the speed of towing even on a flat summer day, and sometimes I even use the same small foils that I do when towing. Surfing the e-foil is an art. Learning to accelerate and decelerate with backwash is like using a motorbike on a track where the berms move. There’s a challenge there which I find pretty cool.

Prone is perfect for good surfers to transition to foiling. It’s a natural step where you don’t have to relearn everything. For me though, prone is the least interesting when it comes to manual riding. I’d rather be on the SUP because my goal is to go far and get a long ride. Something about being in footstraps and already up in the right spot on the board is just very productive for me. I’ve got a family, I’ve got work, I want to be productive on the water.

Towing is the pinnacle. For me, it’s e-foil, stand up, tow in. Something about riding a smaller wing and having to be closer to the power source of the wave. There within lies the mastery.

Kjell: I had the opportunity to downwind with Dave Kalama last summer in the Gorge. It was amazing to watch that level of mastery you’re talking about live and in person.

Laird: Surfing is all about water reading. Downwinding is an interesting discipline because the energy is elusive. Good downwind foilers are good water readers that can carry their energy into the next piece, and the next…

Kjell: The berms are moving!

Laird: That’s right. Stay with ‘em and harness all they have.

Kjell: Let’s touch on Laird Apparel, which is one of several business you’ve got going simultaneously. How did it come about, and what’s your role?

Laird: The line reflects what I need. When you look at the market, a lot of what’s out there doesn’t reflect what I need. Functionally based clothing is what I want, really. Certainly aesthetics are an aspect. That’s where the line came from; there wasn’t anything out there that I wanted or needed. Since Covid, and starting even before then, we’ve gone exclusively online. We have a plan to ramp things up after everything we’ve learned from the past two years. That said, I love the products. All the projects I’m involved with stem from some authentic birth. Whether it’s Laird Superfood or XPT, it all comes from a genuine need or interest. With the opportunities that have come my way, I’ve always tried to walk the line of authenticity. It’s sometimes not easy to do. To be honest, it can be financially unrewarding when there’s something I won’t promote or endorse. When you first start out in your career, you have to pay your bills and survive, and make compromises along the way. The hardest time to say no is when you can’t, but you have to stand for something. Personally, I’m not a good liar, and I can’t promote something I don’t believe in. As for the apparel, I use it and I have a great working relationship with Will, our designer. Of course, I don’t use every single thing that’s in the line, same with Superfoods, because it’s impossible to make only things I use or want. You have to make it for other people, too.

Kjell: It’s a bit like foils, isn’t it? Can’t just have the high performance one you’d use at Nazaré, we need that accessibility factor.

Laird: Absolutely. You have to make the big one. I’d use them all if I had time, but I’ve only got so much. I have to stick to my focus. We all have to find and stick to our focus. At the end of the day, we have to be inspired. If you’re not inspired, don’t bother. You stay true to yourself that way. If you do that, then it’ll never not be fun.

Kjell: That’s where foiling has opened my life in so many ways. It’s a continual source of inspiration.

Laird: Do what you haven’t done. When you’ve been doing something for over 50 years like I have, and you still feel like you’re discovering new things, that’s when you know it’s more than just a sport. It’s an art.

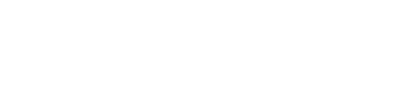

Big thanks to Laird for generously sharing his time and insights. Find Laird Apparel exclusively online at lairdapparel.com

Now subscribe to the world's best foiling magazine!

To get the latest premium features, tests, gear releases and the best photojournalism in the world of foiling, get yourself a print subscription today!